Growing Out of It

On the value of letting kids be weird

When I was five years old I developed a fear of fire. And by fear I mean full-on, screaming terror every time I saw a live flame. Literally overnight I went from feeling fine in the presence of fire, to freaking out if someone lit a match.

My fear created some problems for me and my family. First, we were Catholic. Every week we spent over an hour in a confined space full of burning candles. Second, my father and nearly every other adult at the time was a cigarette smoker. This was back in the days when you could smoke in the grocery store. My father could avoid lighting up around me, but other people were flicking their Bics everywhere we went. Third, we heated our home with a fireplace. One of our favorite family activities was lighting a fire, sitting on the couch with a big bowl of popcorn, and just cozying up on the couch. My parents, family, and entire community were now dealing with a kid who couldn’t stop screaming every time she saw fire.

Interestingly, in psychiatric terms, there was no known onset to my phobia. I hadn’t witnessed a fire, heard about a fire harming another family, or been harmed by a fire myself. Even more interestingly, my parents didn’t go looking for a cause of my sudden overwhelming fear. My parents were raised during the depression and both were the youngest children of large families. They had been through a lot and had heard about a lot more than that. Over the decades they had known countless children and had witnessed many people growing up. They, along with my aunts and uncles and most of the parents in my community, knew some things for certain. One of which being that kids are weird in all sorts of ways and the vast majority of them simply grow out of whatever weird thing they are doing.

I don’t remember anyone being too concerned about my rapid-onset weirdness. What I do remember is being told I would grow out of it. My parents and relatives kindly made accommodations for me. My dad started smoking outside and eventually stopped smoking altogether. Family and community members were informed that I was going through a fear of fire which I would eventually outgrow and this is why we were all acting a bit weird at the time.

I accompanied the family to Mass every Sunday, holding my mother’s hand as I walked with my eyes closed to the pew. Once we were seated, my father made me a little nest under his coat where I was free to daydream through the ceremony, safe from the sight of burning candles. We left the building in a similar fashion, me walking with my eyes closed, my parents socializing with friends while explaining I was going through a fear of fire. “She’ll grow out of it,” was the common refrain.

Family nights around the fire were not canceled due to my phobia. My parents would inform me they were about to build a fire. I took this as my cue to put my head in the corner of the couch, butt facing the fireplace, so my father could place two blankets crocheted by my grandmother over me to keep me safe from seeing the flames. Bits of popcorn were handed to me in my hiding place by my brother and sister, despite my mother’s concern that eating popcorn in this position would create a mess and should be discouraged.

My phobia came to a head one night when we went to an outdoor candle-light vigil. It was January 22, 1976, the third anniversary of Roe v. Wade. My parents were the co-chairs of Pennsylvanians for Human Life and were responsible for organizing the entire vigil. They were very busy and had forgotten to plan around the weird thing I wasn’t finished growing out of. My sister and brother and I had been informed of the vigil and knew we would be going. We were told there would be cookies and cocoa afterward. There was no mention of candles.

I was psyched! I did not realize I would need to endure a sea of people holding candles and mourning lost souls before getting cookies and cocoa. It was too much. I started panicking, shaking, crying in a crescendo that threatened to soon become a scream. Before my mother could get any more stressed than she was from organizing the event, my father picked me up, encouraged me to close my eyes, and walked to find some friends to help him trouble shoot the situation. They hung their coats over a bench to create a little cave where I could wait out the candle portion of the vigil in safety. As I crawled in, my father explained he would stand beside the bench the entire time. I could peek out and see his shoes any time I needed to make sure he was still there. I remember singing along to some church songs while under the bench, then I wriggled out for cookies and cocoa when my dad said the candles had been extinguished.

I don’t remember being afraid of fire after that. I grew out of it, just like everyone said I would.

Most parents no longer have wisdom gained from running around in herds of other developing humans during their own childhoods. We are several generations out from big extended families and wild childhoods being the norm. Few people stick around their hometowns long enough to see their peers who went through weird phases grow into functional adults. Fewer still have trusted elders with intact instincts and long memories to consult. These days, people trust the science. Respected expertise comes from years spent in masters or doctoral program, not years spent raising many children. When confronted with a kid who suddenly can’t stop shaking and screaming every time she sees fire, not seeking expert help through the mental health industry could result in friends or neighbors or teachers or anybody calling child protective services.

Had I been born 40 years later, my parents would have had access to experts and professionals to consult and treat my phobia. Medical insurance would pay for this treatment, but only after I was properly evaluated and diagnosed with one or (most likely) more psychiatric illnesses. If you research how to treat a child with a phobia, you will see that the “she'll grow out of it” approach has fallen out of fashion.

Social workers and counselors reading this are likely thinking, "your parents were helping you practice cognitive behavioral therapy, which is exactly the correct therapy a child with a phobia needs.” And I don’t even know how to articulate just how wrong this assessment is and how tragically it elucidates the destruction of parental wisdom and instinct, the loss of intact intergenerational community, and the extinction of wild, unmanaged, (dare I say) free childhood.

Had credentialed professional expertise been involved in the communal management of my childhood fear of fire, I doubt very much I would have grown out of it.

This doubt is grounded in my observation of the young people around me, very few of whom are growing out of their fears. I won’t take credit for being the first to notice or write about it, but the cohort we call Generation Z isn’t faring so well emotionally. You can check out the work of Abigail Shrier and Jonathan Haidt for some good analysis on the topic.

To access professional help for their fears, children must first be diagnosed with disorders/billing codes. These disorders often become identities which children then internalize. Believing you have a psychiatric condition that requires expert assistance and entitles you to government mandated accommodations at school and work is very different from your parents making you a little nest on the couch and your brother and sister slipping you some popcorn while you hide in it.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, family therapy, and play therapy rarely lead to children growing out of anxiety. Which leads to many families of kids going through a fearful phase thinking their children need psychiatric drugs. These drugs change the way a developing brain creates nerve synapses. When given to children, as Robert Whitaker documents in his excellent book Anatomy of an Epidemic, psychiatric drugs used to treat anxiety can actually cause far worse conditions like psychosis and bipolar disorder.

The more therapy and psychiatric drugs our kids receive, the worse the mental health of the population becomes. And this is great news for the 80 billion dollar behavioral health sector of the US economy.

Like the rest of industrial medicine, the mental health industry has become a chronic disease management model. Just as very few people who seek professional help covered by insurance for their high blood pressure actually end up being healed of their condition, very few children treated in the mental health industry grow out of the medicalization of their distress. Those of us working in the health industry would do our souls and our patients a favor by admitting this reality rather than getting defensive about it. It can simultaneously be true that we went into our professions because we had a deep calling to help people, we sacrificed a lot for our credentials, AND we work within a predatory system that wants to turn every single human into a daily lifelong pharmaceutical customer.

I wish I had a clear path to guide parents out of the current mess. The best I can say is stay human. When it comes to your children always trust yourself more than the experts. Try to find some wise elders who remember unmedicated childhoods. Do your best to create community with other parents trying to avoid the over-diagnosis of childhood weirdness. Get your whole family off the internet and into your bodies as much as possible.

Best wishes! As an old soul turning into an old lady, I have to believe humanity will eventually grow out of this weirdness.

Right ON!!!

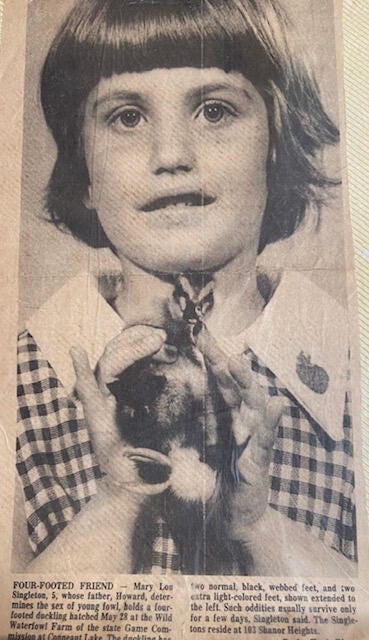

What a good story for letting kids be kids, Mary Lou...